Central to European colonial conquest which laid the foundation for white settler colonialism in ‘conqueror South Africa’(Ramose 2018) since 1652 is the violent dispossession of the land of the Indigenous people by European conquerors. This violent land appropriation (Schmitt 2006) precedes land division which is undergirded by the violent imposition of the (legal) epistemological paradigm of the European conqueror at the expense of African law of the Indigenous people (Jaffe 1957). It is in this sense that we can discern the inextricable connection between the land and law. White settler colonialism through its violent ‘logic of elimination’ (Wolfe 2006) seeks to negate the supremacy of African law as ‘the land of the nation’ (Kunene 2017). Land division (Schmitt 2006) which is premised on the law of the European conqueror laid the foundation for ‘the political economy of race and class’ (Magubane 1979). For instance, the free burghers who worked for the VOC at the Cape became the pioneering ‘white farmers’ as a result of Van Riebeek’s violent dispossession of the land of the Indigenous people. They benefited from the coerced provision of cheap labour by the conquered and enslaved Indigenous people at the Cape and beyond. When Van Riebeek violently dispossessed the Indigenous people of their land he was solidly embedded in the doctrine of Discovery (Miller 2011) which was blessed by several popes as a ‘christian way’ of waging a race war (Wright 1985) on nations outside of the so-called christian Europe.

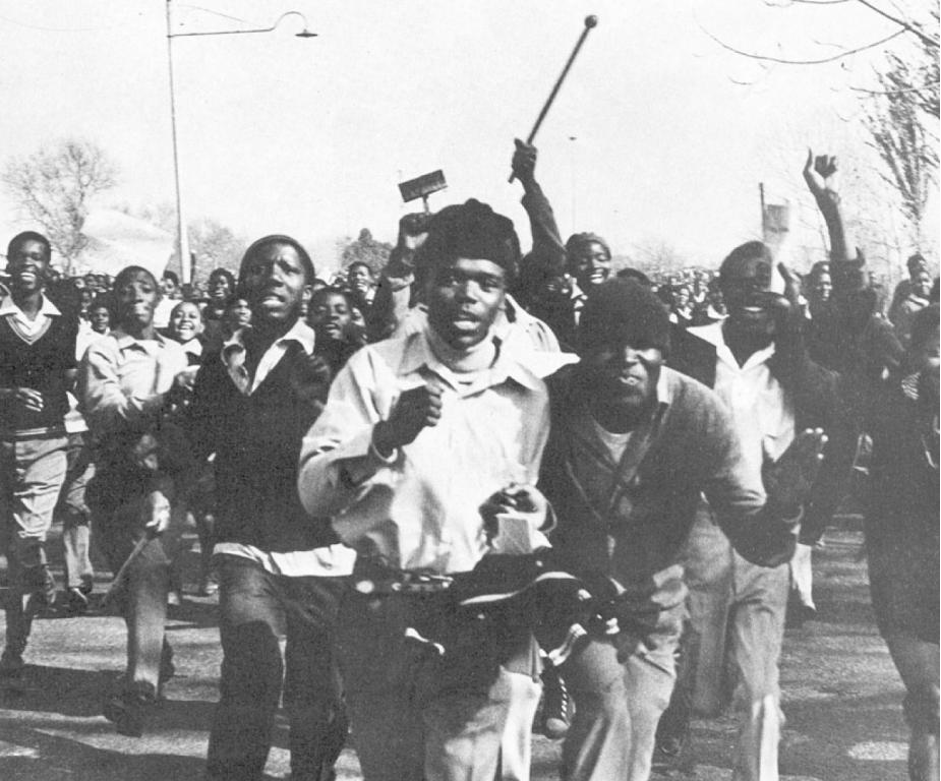

The so-called journeys of discovery were nothing but criminal campaigns by European conquerors whose primary method was violence. It is in this sense that the violence in ‘white farms’ is not accidental to white settler colonialism but it is its inherent trait. The violent nature of white settler colonialism reflects the aggressive essence of European culture and civilization as per ‘the northern cradle’ (Diop 1979 and Bradley 19991). Van Riebeek as the original violent European criminal and vicious founder of the system of ‘white farms’ in ‘South Africa’, once declared that he won the land of the Indigenous people in ‘a defensive war’ and that together with his European bandits, they intend to keep the land (Troup 1975). ‘White farmers’ as the successors-in-title-to-conquest in unjust wars of colonisation (Ramose 2007) by Van Riebeek comprehend very well the significant relationship between violence and land ownership. In reaction to this, some of the Indigenous people also comprehended this relationship as they pursued the search for ‘historical being’ (Lebelo 2020). This search entails the total destruction of whites/abelumbi/wizards and the white settler world through the violence of self-defence as a nation/Isizwe/Sechaba. It is in this revolutionary search that they pre-empted Fanon’s conception of violent decolonisation (Fanon 2001). They understood that whites are violent and that white settler colonialism is innately violent and thus can only be negated through a concomitant violent process. They died violent deaths in this process and their spirits are yet to be avenged by the current generation of the Indigenous conquered people.

When will they arise?

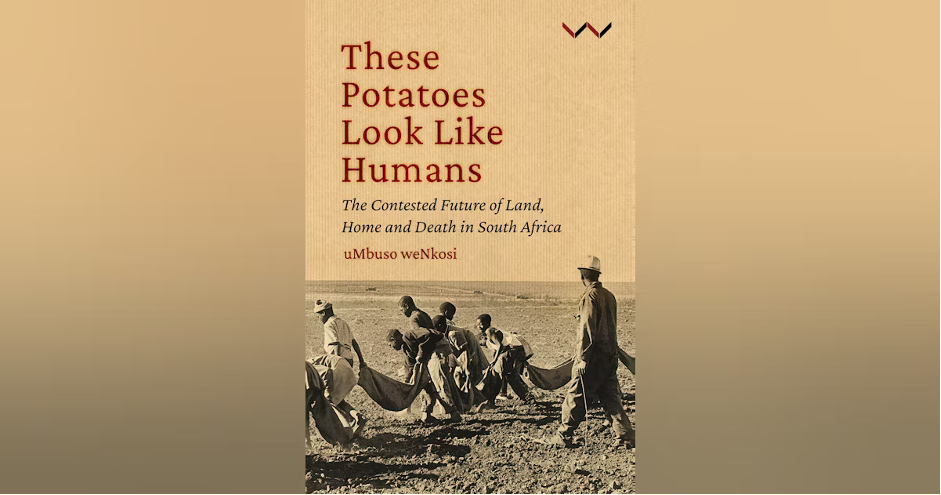

The book under review These Potatoes Look Like Humans: The Contested Future of Land, Home and Death in South Africa, by uMbuso weNkosi is grappling with the above-mentioned question in an indirect way. This is because while the author provides a graphic and honest description of the relationship between violence and agriculture in the context of white settler colonialism, he stops short of recommending a Fanonian decolonisation (as per the first chapter of The Wretched of the Earth) solution to this problem of white settler colonialism in ‘South Africa’. Despite this ‘intellectual timidity’ of the ‘big’ author of this book under review, it is a well-written book. Readers who are interested in the debate about the land question in ‘South Africa’ will benefit from this book’s critique of the reduction of the land question to economics. The author competently extends the land question beyond the realm of political economy and embeds it within the domain of spirituality and belonging in terms of African culture and worldview/’world sense’ (Ani 1994 and Oyewumi 1997). It is in this sense that weNkosi shifts the focus from the anxiety about ‘food security’ which is used by ‘white farmers’ and their spin doctors to pushback against the call for the restoration of the land to its rightful owners since time immemorial, the Indigenous people. While not dismissing the importance of biological sustenance, this book locates the debate about the historic injustice of land dispossession within the realm of African spirituality. This is reminiscent of the ‘spirit’ of Chimurenga against the Rhodesians in Zimbabwe which has resulted in the restoration of the land to the Zimbabweans as the rightful owners of the land of their ancestors.

The book uses the example of Bethal, a white-owned farm on which African labourers were violently exploited and killed by ‘white farmers’ to discuss the relationship between the land, violence and the law in ‘South Africa’. These African workers were forced to plant and harvest potatoes under dehumanising conditions. The logic behind this violent imposition of the regime of slave labour on the farms is the racist notion that blacks are not human. When these ‘humans who look like potatoes’ died they are not buried properly on these ‘white farms’. It is this sense that because of this lack of dignified burials, their bodies come back while other workers are labouring. ‘These potatoes looking like humans’ are actually ‘humans’ who were denied their humanity both while they were alive and dead by the violent white farm-owners.

This book is divided into eight sections which comprise a prologue and seven chapters. These sections are well-structured and coherent, thus making this book a worthwhile read. The prologue is entitled ‘Emazambaneni: The land of terror’ which is about the origin of the book and the centrality of violence, law, and the social order. The violence of the white social order through the imposition of the law of the white settlers is captured by one of the workers who wrote a letter to register the resistance of the workers. WeNkosi (2023: 10) encapsulates the significance of the letter and the core of theme of the book by stating that ‘the violence captured by the letter reflects not only the conditions on the farm but also the social order at large. In looking at violence and law, I contend that violence as law-making is about securing the unknown future.’ ‘The spectre of the human potato’ is the first chapter which provides the historical context of the Bethal scandal of the 1940s and 1950s and the overview of all the chapters of the book. The chapter also introduces concepts and themes which inform the entire book. The conceptual framework in this chapter comprises among other things the native question, paternalism, and the eschatological eye. WeNkosi (2023: 16) captures the overarching theme of the book by stating that ‘in writing about Bethal and the brutality in this land, my aim is to reveal how land ownership and private property ( such as the farm) are linked to violence and contestation.’

Chapter 2 is entitled ‘Whose eyes are looking at history’? This chapter is about the politics of history and methodology in historical research. WeNkosi posits that the victims of violent land dispossession look at their condition through what he calls ‘the spiritual eye’ while white settlers look at it through the paternalistic eye as European conquerors and white supremacists. According to weNkosi (2023:33) the Indigenous people as victims of violent land dispossession use a spiritual eye to look at their land and regard the land as ‘the first and last destiny for their spirit. To create a home and be buried in the land is a spiritual activity.’ Most significantly according to weNkosi (2023:35) ‘the spiritual eye can see the spirits of the dead’ and thus captures ‘the demand of the dead for freedom’ (WeNkosi 2023: 34). ‘Bethal, the house of God’ is the title of the third chapter. This chapter discusses the history of Bethal as a product of white settler colonialism and the labour regime of violent exploitation which was introduced by ‘white farmers’. The chapter also discusses the famous investigation conducted in Bethal by ‘Mr Drum’, Henry Nxumalo to expose the violent exploitation and deaths of black workers on the farm. In line with the theme of violence, law, and the land question, weNkosi (2023:75) captures the libidinal economy of white settler colonialism to this day by stating that ‘therefore, the violence they inflicted was intended to thwart a future violent revolt by the Black people, to keep them docile, to prevent them from contesting the land.’ According weNkosi white settlers live in fear of being ‘attacked’ by the natives who want their land back. Thus, the violence the white settlers use is aimed at securing their future as white masters of the natives in ‘South Africa’. The question is, how long will white settlers continue ‘to live in this strange place’? ‘Violence: The white farmers’ fears erupt’ is the fourth chapter of the book, which discusses white anxiety and the native question. To capture this weNkosi (2023:93) states that ‘the use of violence on South African farms reflected an anxiety about the future in a country where white people are a minority’. WeNkosi (2023:96) concludes this chapter by dealing with the fundamental question of white settler colonialism, the antagonism between the native and the settler who according to Fanon (2001) ‘are old acquaintances’ by stating ‘much more important, however, is that while the farmers positioned themselves as owners of the land, the same land was occupied by workers and families who regarded it as their home. They would die and be buried on the land.’ As ‘old acquaintances’ the farmers as settlers and the workers and families as natives had already met in the late 1600s when the Indigenous people asked Van Riebeek the fundamental ethical question, if the land is not enough for all of us who should make way, the foreign invader or the original owner’? More than ‘three hundred years’ (Jaffe 1957) later this question of historic justice is yet to be answered to the satisfaction of the Indigenous people. ‘These eyes are looking for home’ is the fifth chapter which discusses how the violence of white settler farm-owners seeks to negate the collective identity of the Indigenous people and denying them the foundation to have a society. But despite being subjected to the ontological violence of being called ‘kaffirs’ by paternalistic white settlers, weNkosi (2023:113-4) states that ‘beyond the national and global resistance that was already shaking the South African landscape, there was one thing that always bothered the farmers: the Black farmworkers recognised the farm as their home.’ The penultimate chapter is entitled ‘Bethal today’ which discusses the interconnection between the history of Bethal and its consequences for the present generation of workers. It also underscores the fact that the current generation of workers still regards Bethal as their home. They are haunted by the living past of their ancestors. WeNkosi (2023:120) encapsulates this by stating that ‘in considering all the farms in northern Bethal, where the labour tenants speak of encountering many unmarked graves, I cannot help but wonder whose ancestors those are. These are living dead beings...’

The last chapter is aptly entitled ‘Our eschatological future’. This ‘concluding’ chapter discusses the relationship between violence and the future. It underscores the persistent antagonism between the workers and farmers who regard the land as their home. It highlights the fact that white settlers use violence to dispossess the Indigenous people and still use it today to retain the land as Van Riebeek declared in the late 1600s. It also focuses on the spiritual link between the land and justice. WeNkosi (2023:132) affirms this by stating that ‘those who died remained on the land and were resurrected; they came back looking like potatoes…an encounter with spirits that refused to be forgotten and demand justice.’ The book makes an opportune intervention into the land question in the so-called post-apartheid era, by stating that ‘this spiritual future always refers us to the past. As we discuss land expropriation without compensation, there is need to look into the meaning of land beyond its material value’ (weNkosi 2023:133). ‘The ontology of invisible beings’ and ‘triadic ontology’ (Ramose 1999) which center the inextricable connection between the living, the living-dead and the yet-to-be-born should inform the debate on the land and national question. Chimurenga/war of liberation should be foregrounded. As weNkosi (2023:136) states it ‘those who do not retaliate through violence are in the space of nothingness or invisibility.’ All ’the dead will arise’ (Peires 2003) because ‘even the ancestors are fighting for the land’ (weNkosi 2023:132).

Masilo Lepuru

A Researcher and founding director of the Institute for Kemetic and Marcus Garvey Studies (IKMGS).

Bibliography

Ani, M. 1994. Yurugu: An African-centred Critique of European Cultural Thought and Behaviour. New York: Africa World Press.

Bradley, M. 1991. The Iceman Inheritance: Prehistoric Sources of Western Man’s Racism, Sexism and Aggression. New York: Kayode Publications.

Diop, C. A. 1979. The Cultural Unity of Black Africa: The Domains of Patriarchy and of Matriarchy in Classical Antiquity. New York: Third World Press.

Fanon, F. 2001. The Wretched of the Earth London: Penguin, 2001.

Jaffe, H. 1957 Three Hundred Years: A History of South Africa. South Africa: New Era Fellowship.

Kunene, M. 2017. Emperor Shaka the Great: A Zulu Epic. South Africa: University of Kwazulu-Natal Press.

Lebelo, S. M. 2020. Finding Mangaliso: A desire to rediscover the ‘real’ Robert Sobukwe, BKO July 2020 issue 4 number, pp 49-51.

Magubane, M. B.,1979.’ The Political Economy of Race and Class in South Africa’. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Miller, R. J. 2011. “The International Law of Colonialism: A Comparative Analysis.” Lewis and Clark Law Review 15 (4): 847–922.

Oyeronke, O. 1997. The Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses. New York: University of Minnesota Press.

Peires, J. 2003. The Dead Will Arise: Nonqgawuse and the Great Xhosa Cattle-Killing of 1856-7. Cape Town: Jonathan Ball Publishers.

Ramose, M.B. 1999. African philosophy Through Ubuntu. Harare. Mondi Books Publishers.

Ramose, M. B. 2007. “In Memoriam: Sovereignty and the ‘New’ South Africa.” Griffith Law Review 16 (2): 310–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/10383441.2007.10854593.

Ramose, M. B. 2018. “Towards a Post-Conquest South Africa: Beyond the Constitution of 1996.” South African Journal on Human Rights 34 (3): 326–41. Towards a post-conquest South Africa: beyond the constitution of 1996 .

Schmitt, C., 2006 ‘The Nomos of the Earth in the International Law of Jus Publicum Europaeum’, New York: Telos Press Publishing.Troup, F. 1975. South Africa: An Historical Introduction: Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books Ltd.

WeNkosi, M. 2023. These Potatoes Look Like Humans: The Contested Futures of Land, Home and Death in South Africa. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

Wolfe, P., 2006. Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native, Journal of Genocide Research (2006), 8(4), December, 387–409.

Wright, B. E. 1985. The Psychopathic Racial Personality and Other Essays. Chicago: Third World Press.